Introduction and Health Warning

This note is a first draft: writing down thoughts helps clarify them, and so I lay some down here as a jumping off point. Please think of it as a conversation starter rather than the final word; indeed, please join with me in chewing on this topic and send me feedback.

The purpose is not to provide a fully formed stock pitch, but instead to understand the economics of a new and innovative business model in an industry that only recently did not exist.

Conclusions:

Here are some of my conclusions:

- RPX’s model is the most rational way for firms to deal with the threat of patent trolls. Defensive acquisitions cut out significant legal fees, and consortiums create a stronger bargaining position to help the industry capture that value. The difficulties of colluding given the information assymetries between different players mean, however, that firms need an independent actor, like RPX, to act on their behalf.

- RPX’s refusing to litigate on patents, even against non-members, could aid client recruitment, rather than hinder it. Firms still have a strong incentive to become members as they can influence the whole RPX budget to acquire patents which disproportionately benefit them, even if there is some further shared benefit for others. Given this, the economics of refusing to litigate on patents means that RPX gains scale advantages which it otherwise would not.

- Beyond such advantages, RPX appears to benefit from several other scale and network advantages. This should help it to ensure that it can fend off competition.

- Although RPX seeks to mitigate the social damage done by patent trolls, it nevertheless is reliant on their existence to have a continued purpose. Were the US government to take more concerted efforts to solve this problem directly, the economic value of the moat that RPX has built up could quickly evaporate.

RPX’s business – an overview

RPX has evolved into providing a few distinct services that attempt to reduce costs and make life easier for corporate legal departments. The vast bulk of its revenues and earnings, however, come from subscription fees paid to its defensive patent acquisition service; it is this business that is the focus of this memo. From now on, when I refer to RPX it will be to this particular segment of their business.

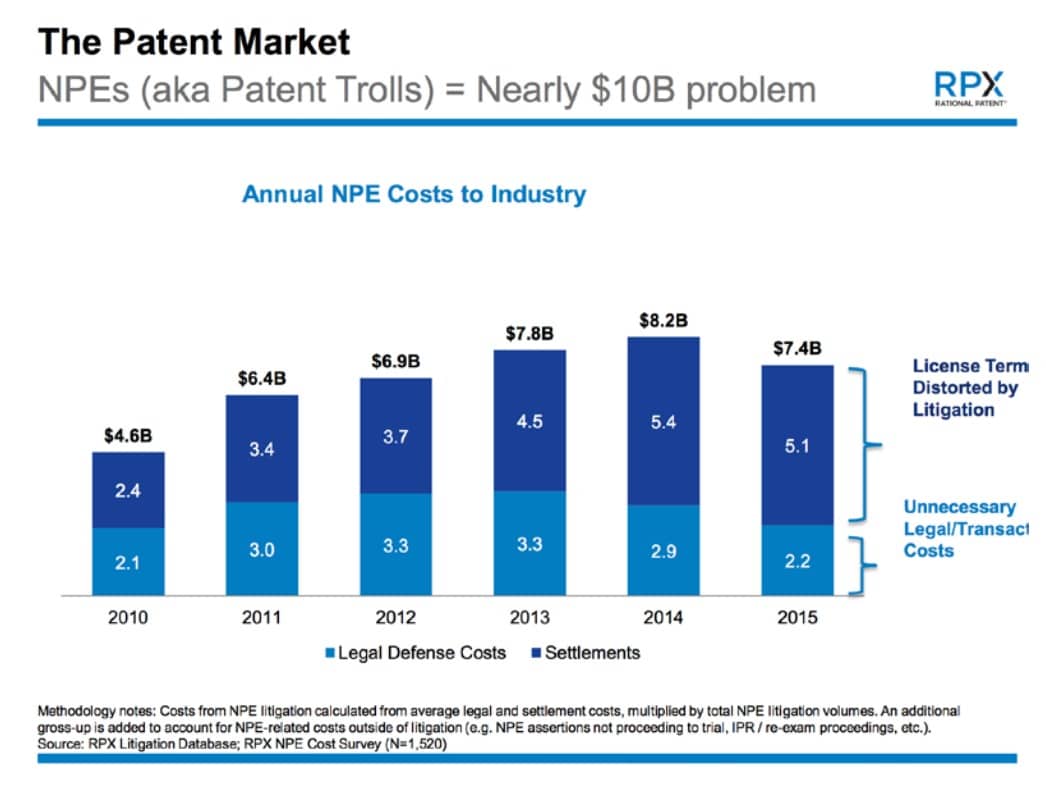

To understand RPX, it is first necessary to outline the growing phenomenon of ‘patent trolling’, to which they provide a response. As software and technology have become an increasingly large and sophisticated part of the modern economy, the extent to which hundreds or even thousands of patents have become applicable to common products has increased dramatically. A phenomenon has emerged, primarily in the US (due to its distinctive legal system and strong intellectual property protections), whereby non-practicing entities (NPEs – the patent trolls) are set up to acquire patents with the sole purpose of litigating on them. Given the sheer number of registered patents, firms are unable to easily confirm that a planned product does not infringe a single one; they therefore often go ahead and enter production blind as to whether they will be relying on someone else’s intellectual property. This provides a significant number of targets for the patent trolls, with firms unable to alter product designs easily once they have sunk costs into design and production. Typically, these NPEs acquire patents, and then litigate many firms at once in the hope of extracting a ‘reasonable royalty’ award. SimpleAir, an NPE, sued multiple firms for a patent that was used in the sending of push notifications; many settled, but when Google didn’t, it was initially ordered to pay SimpleAir $85mn at trial, before the decision was later overturned. The patent in question described a failed company’s 1996 desktop notification system; the supposed infringement was by Google’s Android operating system. RPX estimates that the costs this problem presents to practicing firms was close to $8bn in 2015, with much of this driven by legal and transaction costs which both the NPEs and the target firms have to pay regardless of the outcome of any dispute.

RPX aims to help protect firms from NPEs by buying up patents prophylactically, so they cannot be used in litigation. The key elements of its approach are as follows:

- Firms are charged a fee based on a set rate card, with fees increasing with a firm’s revenues and profit levels. Once a firm is locked into this structure, RPX guarantees not to increase the rate card charges at a rate higher than consumer price index inflation.

- RPX uses the membership fees, after taking a cut and paying its costs, to acquire patents, attempting to build a portfolio that will help the spread of members in its network.

- RPX promises not to litigate any firm, member or not, on the patents it holds.

- Companies initially get a 3 year license on all RPX patents if they become members, and if they stay with RPX long enough these licences become perpetual. These licenses are relevant because, although RPX promises not ot litigate on the patents, they are legally entitled to sell the patents to another entity who might.

- RPX gathers confidential operating data from each of its members, which it does not share, to help it decide which patents are the best to pursue. It also collects information on pricing offers made to member firms when patents are up for sale, to improve its bargaining position.

RPX has over 250 clients, with the client base dominated by technology-focussed blue-chip companies such as Google, Samsung, IBM and Cisco. Founded in 2008, it is by far the largest entity providing such a ‘defensive acquisition’ service, and the only major private firm involved in such activities. Its main competition comes in the form of patent buying consortiums, such as the not-forprofit Allied Security Trust (AST).

RPX is the dominant form of defensive patent acquisition in the market at the moment, having facilitated the acquisition of more than 5x the amount of patents (measured by value) that AST has (the largest active consortium today). It is profitable, and appears (depending on the assumptions made to calculate true economic replacement value in the Greenwald style) to be generating an economic ROE of somewhere in the range of 20-40%, well in excess of its cost of capital. Below I shall attempt to examine why this might be the case, to try and evaluate whether this is a signal of a durable competitive advantage, both against other business models in this area and against any possible clones, or instead perhaps just a temporary reward for moving into this new industry first.

Why should firms defensively acquire patents in the first place? Why collude?

To understand the drivers of this business, it is first worth ascertaining why firms might be interested in such a service in the first place. RPX estimates that by serving as a collective purchasing agent for defensive patents, it has saved $3.2bn in expected costs for its members by acquiring (or facilitating the acquisition of) $2bn of patents, creating $1.2bn of value. Below I set out how that might be possible.

The benefits of consortiums and collusion in defensive acquisitions

Given that patent trolls often acquire a patent with the intention of suing multiple firms in the industry at once, the expected value of the patent to them in net expected settlement fees will likely be much larger than what one firm is willing to pay to avoid their portion of the settlement fees and legal fees. One option would be for such a firm to buy the patent, issue itself a perpetual license, and then sell it on (called a catch and release strategy).

There are good reasons to believe that a collusive approach would be more effective. The first clear benefit is reducing transaction costs; by buying the patent just once as a group, you reduce the search and transaction costs involved that would result from each firm buying it, issuing a license to itself, and selling it on.

Further, by creating a monopsony, you improve the bargaining power of the industry which should increase the amount of the value captured by avoiding legal fees; this is important, as the uniqueness of each patent means that every seller is an automatic monopolist. Consider the scenario outlined above. If an NPE owned the patent, and there were many firms competing to buy it, that NPE might force them to bid the price up to $125mn2 (i.e. their reservation price). If they were to team up, they might be able to force the NPE down to its reservation price of $75mn, and capture almost $50mn of extra value. When the value created by eliminating legal fees is so large, the importance of this increased bargaining position is very significant.

Finally, by pooling the expected benefits of reduced legal fees into a single entity, your ability to outbid other actors in the market increases; thus even if an NPE overestimates how much a patent can earn in settlement fees, you could outbid it and create value if the collective value of reduced legal fees was greater than the margin by which the NPE was overestimating.

Why does RPX allow non-member firms to free-ride?

One of the most startling initial features of RPX’s business model is that it does not litigate on its patents against firms which are not members; this seems to be turning down a free lunch, as well as depriving the business of a way to encourage more firms to be clients. While in refraining from doing so RPX sets itself apart very clearly from the excesses patent trolls, I would be surprised if the decision was taken for puritanical reasons alone; the firm’s founders were high-profile executives at patent troll firms prior to setting up the company, and, as explained in the ‘Concerns’ section below, are reliant on patent troll activity for their firm to have any purpose at all. It does appear, however, that there are plausible economic reasons for such a policy.

It is plausible that such a policy actually helps attract more clients than a policy of implicit blackmail, via threat of litigation, would do (I will explain below why a client would ever want to join in the first place if they have an option of free-riding on the benefits of others). The first reason this could be the case is one of information asymmetry. RPX gathers data from its clients, and then claims to purchase patents which will be most likely to help them avoid exorbitant costs. When it promises not to litigate on those patents, the only way it can generate revenue is by keeping those clients happy; by buying the best possible patents, so that clients feel they have a good service. Given that RPX is better able to evaluate the worth of patents than the members, to some extent they have to trust that RPX is purchasing the best patents possible (although importantly they have some limited ability to check if this is true). By ensuring that there is no independent reason to buy patents for RPX (i.e. it could benefit independently by earning money from the patents it acquires as well as via fees), they guarantee that the money they see being spent on patents is well spent. While RPX can of course abuse their membership fees in other ways (for instance by not buying patents at all and paying out the fees to shareholders as a dividend), this is much easier for firms to track.

Another reason RPX might want to do this to attract firms would be to mitigate an inherent disadvantage in its model (from the members’ perspective) vs. forming a more directly owned consortium among themselves. For, although they are the ones putting up the cash to buy the patents, they do not receive immediate ownership; indeed, they only get perpetual licenses after having been members for several years (whereas AST, for instance, awards immediate perpetual licenses to its members). RPX clearly feels there is an advantage in this approach in that it encourages members to remain members for several years once they have joined (and it indeed enjoys 90% renewal rates). However, before joining in the first place, members might want some guarantee that if they change their mind on the value of the service, they can leave after a year without a high likelihood of being sued over a patent that they helped RPX acquire. This commitment by RPX reduces the chance that this will happen (without eliminating the chance as if the patent was later sold on to another entity, it could be used in litigation, providing some remaining incentive for members to wait for the perpetual license).

2 I gloss over some adjustments that would have to be made here for this example to work perfectly in an industry where there are multiple firms, but hopefully the above discussion is intuitive enough. These adjustments wouldn’t change the thrust of the concusion.

Why does anyone ever sign up to RPX?

Recall that the premise behind consortiums in the first place is that multiple firms can benefit from avoiding litigation based on a single patent. If an effective guarantee is provided by RPX on nonlitigation regardless of whether firms contribute cash to its acquisition, it would initially seem that firms have a strong incentive to free-ride on each other, and not sign up to the service. As outlined above, the license clearly provides some value in the rare case that RPX sells a patent on; I struggle to see, however, how this provides sufficient motivation for firms to pay the c. $250mn in membership fees a year that they currently pay.

There are two scenarios, which plausibly apply to a large number of cases, where the free-riding problem can be solved. The first scenario occurs when a patent cannot be bought by the consortium (RPX) unless multiple firms are involved. Consider a case where where a patent is up for sale for $4mn. For the reasons outlined in the section on the benefits of defensive acquisition, it is plausible that the benefits to two large firms who might be targeted by this patent of acquiring it defensively could exceed this figure. Let’s say they would each get $3mn in benefit; they could then each put $2mn towards its purchase and make an economic gain of $1mn. Given that RPX will not litigate on the patent, neither firm has an incentive to buy the patent unless the other also participates (if they pay $4mn alone they lose out, but if they pay $2mn each they gain). Both pariticipating is clearly the ideal scenario for the firms, with neither firm having an incentive to deviate; if one pulls out the other won’t go through with the deal, and both will lose out on the $1mn gain. The condition is therefore this: if my participation is critical to the deal going ahead, I will not try to free-ride as the deal will not go ahead without me.3

The most important scenario, however, is the one where there are varying degrees of benefits from the defensive acquisition of patents to actors. The purpose of this analysis is to set out what RPX means when it says that firms join to ‘influence its acquisitions’, and the conditions that need to be met for this motivation to make sense. By ‘varying degrees of benefits’ I do not mean that a single patent has different value for different actors; in general this is the case, as larger firms have more to lose in potential damages. Rather, I mean that the way in which patents help different actors differs itself across patents which still help the same actors. To clarify, consider the following example of an industry with 3 firms, which are all at risk from two types of patents (A and B). I shall show a distribution of values to the 3 firms which I would call a ‘non-heterogenous case’ and one which I would call a ‘heterogenous case’. If a patent has values 5, 3, 6, that means it has a value of $5mn to firm 1, $3mn to firm 2 and $6mn to firm 3.

Non-heterogenous case:

Patent-type A value: 4, 4, 2.

Patent-type B value: 8, 8, 4.

Heterogenous case:

Patent-type A value: 4, 4, 2.

Patent-type B value: 2, 2, 6.

With this illustrative example, we can demonstrate why a firm might free-ride in the nonheterogenous case but not in the heterogenous case. Assume that all patents can be bought for 70% of their total value to firms (this would reflect their willingness to pay being above market price in a way similar to that outlined in the section on why defensive acquisitions make sense). Let’s say that each firm has $70mn in cash. If firm 3 doesn’t participate, firms 1 and 2 (in the manner of the first scenario) could both be expected to purchase 20 lots of patent-type a for $7mn each, and would see a welfare gain of $20mn (each patent they buy is worth $1mn more than it costs to the two of them combined).4 Given this, firm 3 could consider joining in by buying 10 lots of type A. This would only give it a marginal benefit of $20mn, for a cost of $70mn, and so even though it would be welfare increasing for the industry, and even though it is free-riding off firms 1 and 2, it will not choose to do so, assuming that firms 1 and 2 have no extra cash to compensate firm 3 for doing so.

The heterogenous case is very different. Under the scenario where firm 3 refuses to participate, firms 1 and 2 will buy 20 lots of type A patents as before, with the resulting utilities for each firm:

Firm 1: 20 x 4 + 0 = $80mn

Firm 2: 20 x 4 + 0 = $80mn

Firm 3: 20 x 2 + 70 = $110mn [firm 3 still has cash left over so this is added to its end utility].

However, were firm 3 to join the consortium and get firms 1 and 2 to commit to buying more of patent type B with their money, the following outcome is possible, assuming the consortium as a whole buys 17 type A patents and 13 type B:

Firm 1: 17 x 4 + 13 x 2 + 0 = $94mn

Firm 2: 17 x 4 + 13 x 2 + 0 = $94mn

Firm 3: 17 x 2 + 13 x 6 + 0 = $112mn All firms are unambiguously better off (total welfare for the industry has increased by $30mn)5 . The heterogeneity effectively allows firm 3 to internalize the positive externality of buying a patent and not litigating on it, by using it as leverage to encourage the other firms in the industry to buy patents which help it more than would otherwise be the case. In the non-heterogenous case, the other two firms have nothing to bargain with to encourage it to join the consortium, and so the externality cannot be internalized. It is perfectly plausible that the heterogenous scenario could arise: consider two firms operating in two distinct industries together, but with different weightings in each (e.g. Apple and Lenovo, where both make phones and laptops but with different biases to each product). That would mean the relative harm of a phone patent vs. a computer payment being litigating on by an NPE would differ in a way not dissimilar to the scenario above. It’s worth noting that another important part of the above example is the fact that there were lots of different patents to buy which the firms could reallocate their resources between; if there weren’t, then the solution wouldn’t work. This further helps explain why RPX has a lot more success recruiting members who fall foul of multiple patent lawsuits a year.

3 There could be small firms who free-ride and the deal could still go ahead; what is critical is that they could not step in to make the deal go ahead if I pulled out. So if there was a firm who got $50k of benefit from the deal going ahead, they would not change the game significantly and would likely free-ride. If there was a firm who got $1.5mn of benefit, they could cause a more serious problem, as any one of the three largest firms could pull out, and the deal would still be worthwhile for the others to go ahead with, assuming the patent still only cost $4mn. The fact that being a ‘tipping point’is important helps to explain why many of RPX’s clients are large firms.

4 Or they could buy 10 lots of type B; given that this patent type is just a linear scaling of A in the non-heterogenous case, I will ignore it from now on.

The RPX moat

Having now understood why RPX’s model has come to dominate the defensive patent acquisition space, we can begin to see the network advantages it brings. Several immediately spring to mind:

- All the reasons given for forming a consortium above are also reasons to prefer a larger consortium to a smaller one. The larger the network, the more bargaining power you have when acquiring patents. It would be tough for a competing entity to get the same deals for members of RPX if it didn’t have the buying power, and thus it is unclear why a member would want to defect without all of the others.

- The importance of the ‘heterogeneity’ analysis is not only to show why firms join in the first place; it also demonstrates a network advantage in this business. The more firms there are already in the RPX network, the more of the positive externality of a possible firm 3-type entrant into the network can be internalized, and thus the more leverage they have to get the others to buy patents which favour them more. Thus, if deciding which network to join in such a scenario, you will choose to go to the one with the greatest pot of money which you can sway (i.e. the one with the most members). Interestingly, this important part of the moat would fall away if RPX litigated on its patents, as all positive externalities could quickly be internalized by actors within its memberships (if it was to pay out litigation fees).

- The scale allows you to pool information about patent risks and pricing between different players, as well to spread the fixed cost of researching threatening patents over a broader number of participants.

The dominant position RPX has come to achieve in the industry appears fairly defensible, even if a copycat comes along.

Concerns

The above is an attempt to understand how RPX works, and what its economic advantages might be. As a stock, however, there would be several concerns that need following up:

- It’s symbiotic relationship with patent trolls. RPX has suffered in the past year as legislation to crack down on patent trolls has (somewhat) weakened demand for its services. That risk appears to be abating for the time-being, but it’s business model does at heart seem reliant on a dysfunction in the US system that is not present elsewhere in the world, even if it is only reliant on it to the extent it is trying to mitigate it. A parallel to Valeant can be drawn here; if you only make money through something which is socially detrimental (which I believe patent trolls are), you should expect to be shut down sooner or later: RPX is at risk if the patent trolls are legislated away.

- Capital allocation. The business might be good, but it appears that the recent Inventus acquisition was pricey. The cash used there could today have been put towards repurchasing almost 40% of RPX’s market cap.

- Reality. Much of the above analysis is armchair economics. The extent of the moat will depend, to a large extent, on the extent of the value created by the monopsony/scale/heterogeneity.

Sources and Resources

The Economist on how to solve patent trolling: http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21660522- ideas-fuel-economy-todays-patent-systems-are-rotten-way-rewarding-them-time-fix

Good investigative piece on the RPX business model: https://pando.com/2013/09/09/rpx-and-thecomplicated-business-of-stockpiling-patents-for-good-not-evil/

Harvard Business School on RPX : https://rctom.hbs.org/submission/rpx-corporation-first-defenseagainst-patent-trolls/

Intellectual Ventures, an NPE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intellectual_Ventures

Rockstar acquisition: http://www.rpxcorp.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/03/Safe-HarborHow-Rockstar-pushed-patent-trolls-off-the-stage.html

How RPX gathers data: http://www.worldipreview.com/contributed-article/npes-unlocking-theblack-box-of-npe-risk

RPX VIC Write-up: https://www.valueinvestorsclub.com/idea/RPX_CORP/108134#description

The Allied Security Trust: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allied_Security_Trust

Patent Law glossary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_patent_law_terms

A Cornell paper on defensive acquisition strategies, including RPX and AST: http://eship.dyson.cornell.edu/wp-eship/wp-content/uploads/Delcamp_Leiponen_CMR.pdf

The Google-SimpleAir dispute: http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2016/04/85-million-patent- verdict-largest-ever-against-google-wiped-out-on-appeal/

An interview with RPX’s CEO: http://www.xconomy.com/seattle/2010/05/03/the-future-of-patentwars-more-of-the-same-but-less-litigation-says-john-amster-of-rpx/?single_page=true

Akerlof’s Market for Lemons: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Market_for_Lemons