Introduction and Health Warning

This memo is a first draft, a jumping-off point.

Writing things down helps to clarify my thoughts, so please think of this as a conversation starter rather than the final word. The purpose is not to provide a conclusive stock pitch, but rather to understand the inner workings, competitive landscape, and challenges ahead for the engine leasing industry – one that neither is as transparent nor has received as much attention as its aircraft leasing counterpart.

That being said, I invite you to join me in engaging this topic as food for thought, and would appreciate any feedback. As I learn more, I plan to revise and update this document, and then circulate it back out to you.

Key Takeaways

Here are the key takeaways from my memo:

- While the spare engine market is small compared to the aircraft market, the value of all leased engines represents a significant portion of the commercial aviation finance market.

- Unlike the value of aircraft, which depreciate over a 25-year life, engines can be restored to full initial value as long as assets are properly maintained and managed.

- The aircraft engine business is highly competitive and deals with high buyer bargaining power. While there are high barriers to entry and a low threat of substitutes, competition from Asian entrants and aftermarket MROs may change the engine leasing landscape.

- Despite these challenges, Willis Lease competes strategically through means of its independent ownership, “triple-net” leases, joint venture with a Chinese partner, and recent establishment in the aftermarket to help maximize residual engine value.

- Going forward, in order to stay competitive, Willis Lease must adapt to supply chain integration adopted by competitors, entry of international players, and overall trends in the global aviation sector, including airline consolidation and rise of LCCs

Why the need for aircraft engine leasing?

Historically, commercial aircraft operators owned their spare engines and other aircraft-related equipment. However, as engines become more technologically sophisticated and expensive to acquire and maintain, cash-constrained operators have become more cost-conscious of engine ownership, which requires an upfront lump-sum payment and additional cash injections throughout the engine’s life. Thus, many in this capital-intensive business have transitioned to leasing a portion of their spare engines instead.

Even large aircraft operators who own the majority of their engines have the need for leased engines in times of high unscheduled engine removals, shop visits for life-limited parts (LLP)1 , and other events of such sort. The flexibility to plan removals and warranty issues relies upon the use of leased assets, which can make a significant financial impact relative to the cost of ownership.

For aircraft operators and other engine users, lessors offer many options to convert a high fixed cost into a long-term variable cost. Aircraft operators can negotiate separate “pay-per-hour” deals with different engine lessors, paying them for every hour an engine rather than paying for the engine in one go.

1 Within engine modules are certain parts that cannot be contained if they fail, for they are governed by the number of flight cycles operated. Such critical LLPs generally consist of disks, seals, spools, and shafts.

How about general aircraft leasing?

The engine leasing and financing market is a difficult one to track, partly because of the lack of data publicly available and partly because it does not follow such a clear pattern like the equivalent market for aircraft.

Aircraft lessors thrive in an environment where they enjoy access to low-cost capital, firming aircraft values, improving lease rate factors, and robust global demand for aircraft. The leasing model is fairly straightforward:

1 Purchase commercial aircraft directly from manufacturers

2 Lease the aircraft (approximately 1% of asset value per month depending on aircraft type and age) to commercial airlines around the world.

Various safety and legal agencies will ensure that airlines maintain the planes well over the duration of the lease, which is usually 5 – 15 years. Upon leasing, the lessor is not responsible for maintaining the plane or considering fuel costs, and insurance companies cover compensation in the event of a plane accident. Due to the high threshold of initial investment, there was initial low competition and high barriers to entry for new players, but this landscape is ever-evolving.

How do the two markets compare?

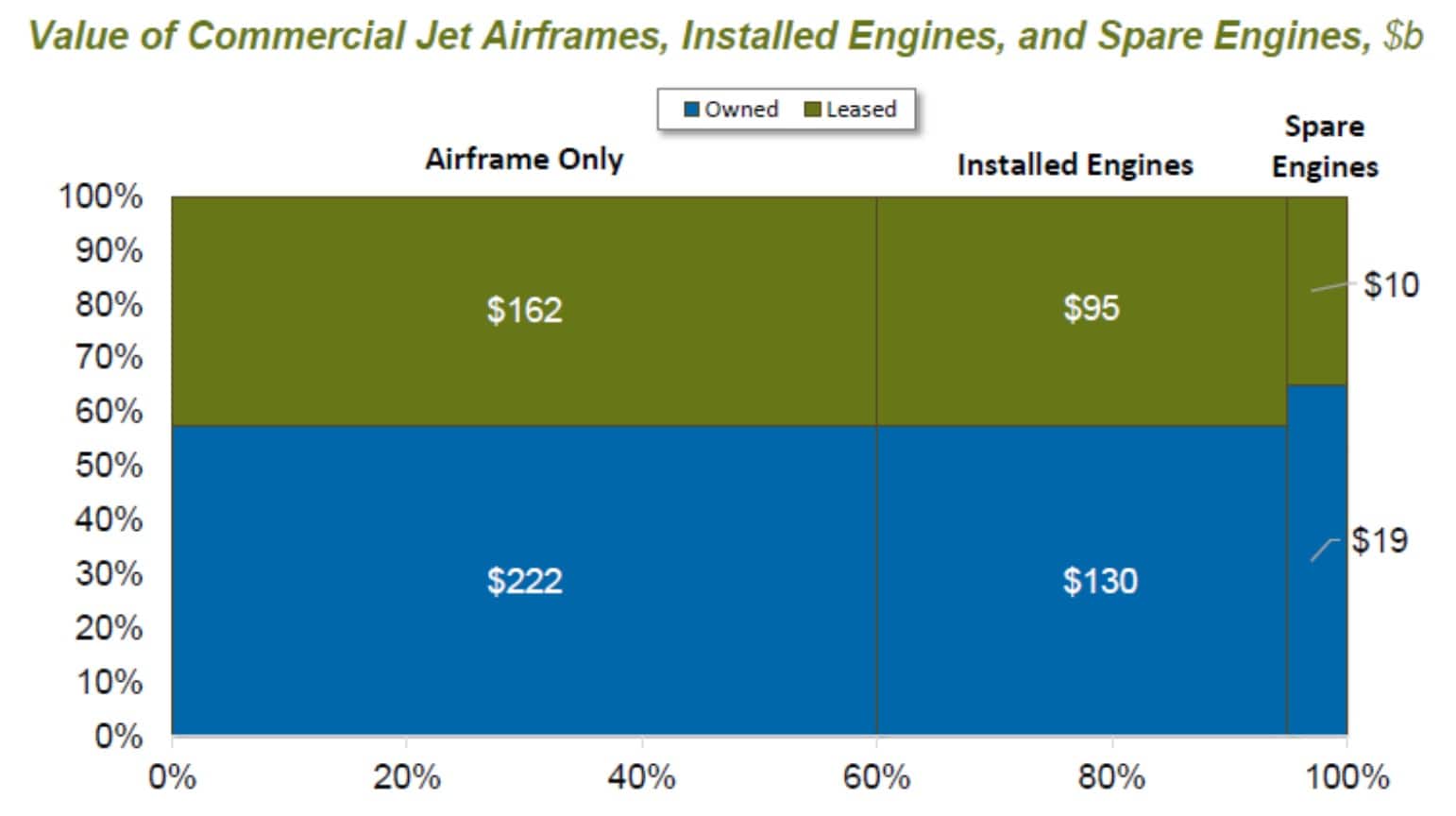

Compared to the commercial aircraft market ($610 billion), which comprises both the airframe and installed engine, the spare engine market is small ($29 billion). Hence, in this past, this has encouraged investors to invest only in aircraft, but not the engine subcomponent.

As it turns out, if we segment engines into installed and spare, then the size of the leased engine market equates to nearly 40% of leasing of all and any parts. Hence, in actuality, the value of engines comprises a very significant portion of today’s commercial aviation finance market. Though, another key point to take into consideration is the difference in value behavior between engines and aircrafts and airframes, and the drivers of such values over their economic life cycles.

How do their asset values differ over time?

An individual engine’s value is based on three major components:

1 Engine shop visit maintenance value2 – related to the time an engine is capable of operating before requiring a performance restoration shop visit3

2 LLP maintenance value4 – related to the cycles each LLP may operate until requiring replacement

3 Core value – accounts for the remainder of the engine value, including the non-LLP and engine data plate

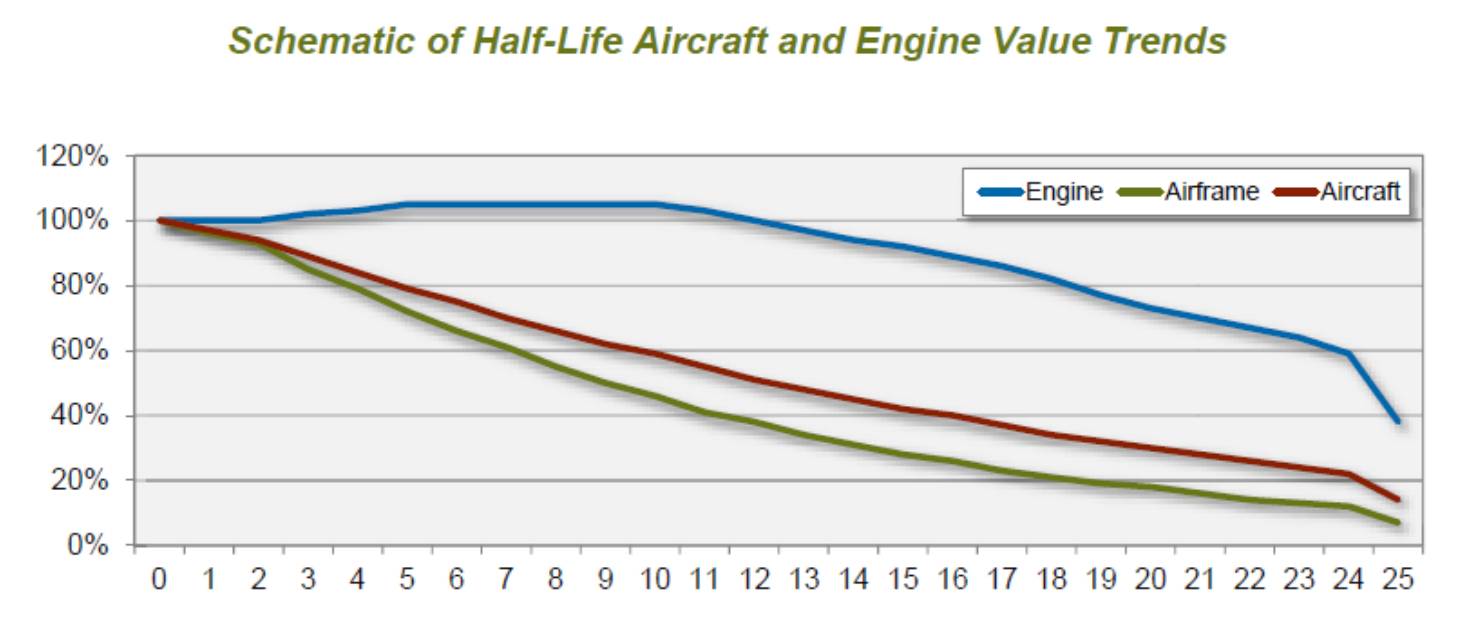

As an aircraft ages, the engine value accounts for an increasingly significant proportion of total value of the whole aircraft. In fact, if we suppose the full functional life of an aircraft to be 25 years, then the relative values of the airframe versus of the engine break even around half-life.

4 Aside from reasons related to operations and value retention, engine maintenance is also required by regulatory authorities to meet at least the minimum standards of inspection and maintenance.

5 The core engine deteriorates as parts are damaged due to heat, erosion, and fatigue. During a performance restoration, the core module is traditionally dismantled and airfoils (rotors and stators) are inspected, balanced, and repaired or replaced as necessary.

6 The rotating compressor and turbine hubs, shafts, or disks within the engine have a specifically defined operating life, at the end of which, the parts must be replaced and not used again

Furthermore, engine value behavior is notably different than the behavior of the whole aircraft and airframe values:

- On the one hand, airframes are very much depreciating assets (typically over 25 years), so materially different values are taken on between 5 and 25-year-old assets.

- Engines, on the other hand, with maintenance, can repeatedly be restored to like-new condition. This means that there is essentially no influence of engine age on value; a 5- or 25-year-old engine in the same maintenance status can have the same value.

Within the engine, the value is heavily influenced by maintenance condition as core values decline. As the engine fleet ages, focus must be increasingly shifted to robust technical and asset management of the engines to ensure that residual value can be captured. Hence, the ability to actively manage assets as they approach end-of-life is essential to maximizing returns in this increasingly sophisticated market.

What factors/challenges affect the engine leasing market?

We can gauge growth and interest in the engine leasing industry by looking at two fundamental drivers:

- The number of aircraft engines in the market; and

- The proportion of engines that are leased (rather than owned) by commercial aircraft operators.

Number of aircraft engines in the market

In its annual market outlook released in July 2016, Boeing forecasts a need over the next 20 years for more than 39, 600 airplanes valued at $5.9 trillion. If we use the market outlook for the aircraft market as a proxy for that of its engine counterpart, we would expect the number of spare engines to increase as well.

Meanwhile, some major players who buy airplanes disagree that the near future is as simple, and paint a far gloomier picture for large jet sales over the next few years. With global airlines facing a glut in capacity and pressure to lower fares, the availability of used airplanes coming off lease only adds to this glut after years of massive orders for new widebody jets.

In other words, too many aircrafts have been ordered to be delivered at the same time; in the Middle East and Europe where widebodies particularly oversaturate the market, airlines will be competing against each other for the same passenger traffic.

Airbus and Boeing5 each have shiny, expensive lines of new-technology airplanes, many of which have been threatened by not only a lack of new orders but also the loss of existing ones. In the record sales years of 2012 and 2013, they together won more than 2,800 net airplane orders. Last year, total sales were half that.

At the annual conference of the International Society of Aircraft Trading (ISTAT)6 , a gathering of aviation financiers and executives of airplane lessors and major airlines, Airbus sales chief John Leahy projected that total sales this year for both manufacturers will be down another 30% to less than 1,000 jets.

In an interview at ISTAT, Steven Udvar-Hazy7 , chairman of Air Lease Corp. and a leading market-maker in the airplane leasing industry, noted that 235 of just over 300 orders for Boeing’s 777X are from the three major Gulf carriers, 150 of them from Emirates alone. Therefore, if these few critical carriers do not perform and reduce their involvement on 777X, then it would have a profound impact on the airplane.

Despite the last few years having favorable conditions for the aviation business – growing passenger traffic, low fuel prices, and cheap capital – the current unpredictability situation in the U.S. and Europe, along with the prospect of rising interest rates and the airplane-capacity glut, give way to a much higher probability of the bubble bursting.

In the long-term future, however, world air traffic is expected to continue to grow. In January, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) reported that global passenger traffic rose 9.6% compared to a year earlier, the strongest increase in more than 5 years.

Aengus Kelly, CEO of AerCap, the world’s largest aircraft lessor, pointed out at ISTAT that every year in Asia, another 100 million people are getting on a plane for the first time. Thus, the inexorable rise of middle classes with money to travel in emerging economies, such as China and India, translates to a greater assurance of the aviation business in the long run.

1 The competition between manufacturers, Airbus and Boeing, has been characterized as a duopoly in the large jet airliner market since the 1990s. This resulted from a series of mergers within the global aerospace industry, which ousted out competition from other manufacturers like Lockheed Martin, Convair, and Fairchild Aircraft in the U.S., and British Aerospace and Fokker in Europe.

2 ISTAT is a non-profit society whose members have common interests in the manufacture, purchase, brokerage, leasing, maintenance, and appraisal of transport aircraft. It holds an annual conference in San Diego, the most recent of which took place over March 5-7, 2017.

3 Steven Udvar-Hazy is credited with creating the airplane leasing industry. He previously was CEO, and now is chairman of Air Lease, his second company in the airplane leasing industry and a major player that went public in 2011. His first, International Lease Finance Corp. (ILFC), was acquired by AIG in 1990 and most recently by AerCap in December 2013.

Engine leasing penetration rate across aircraft operators

For successful engine leasing, the number of spare engines needed to service any fleet is determined by many factors:

- The number and type of aircraft in an aircraft operator’s fleet;

- The geographic scope of such operator’s destinations;

- The time an engine is on-wing between removals;

- Average shop visit time; and

- The number of spare engines an aircraft operator requires in order to ensure coverage for predicted and unscheduled removals

Given the increasing cost of newer engines, the anticipated modernization of the worldwide aircraft fleet, and the emergence of niche-focused airlines with special capital needs, many believe that commercial aircraft operators are finding operating leases to be more attractive than capital leases or ownership of spare engines. Following the footsteps of aircraft leasing, which has grown its penetration to 40%, engine leasing is likely to become more popular over the next 15 years.

Even though an estimated 35% of the world’s spare aircraft engines are leased assets, the industry still struggles when it comes time to return them. Aircraft maintenance costs represent approximately 10 – 15% of an airline’s operating expenses, 35 – 40% of which is engine-related. Of the engine’s direct maintenance costs, material replacement, which accounts for 60 – 70%, is the most significant item because parts wear out and have to be either replaced or repaired.

Aircraft engine lessors, for the most part, are like aviation financial institutions, and typically do not have maintenance or engineering departments. Thus, for a number of reasons, they are not designed nor do they plan for the hassles associated with engine lease returns, which run an industry average of 20 days.

Above all, maintenance and quality departments are usually not involved with the signing of lease contracts, so they are unaware of the contractual requirements for lease return until the engine is ready to come off. This is because 98% of all agreements and contracts are executed by the finance department, who may or may not have the knowledge and background for the technical portion of the lease return. At the end of the day, quality assurance supervisors and technicians have to weed through the barriers to try to get lease return conditions accomplished. In any event, through the guidance of legal administrators, the lessor is inexorably responsible for the leased engine while it is under lessor’s maintenance program.

Once the engine is off-wing, it simply becomes an accessory. Some engine lessors may use large engine maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) companies8 to tend to lease return, but this has its own large pitfalls as well. Lease returns can often be time-consuming, and they do not generate the same high sales numbers as engine overhauls and hospital-type visits. These larger shops are typically very busy, so aircraft engine lease returns get pushed to the end of the line, dramatically increasing lease return time and swelling expenditures.

8 In the aircraft maintenance sector, MRO services involve the inspection, rebuilding, alteration, and supply of spare parts, accessories, and raw materials.

Who are the players in the engine market?

The engine leasing market comprises players all across the aircraft supply chain, from engine and aircraft manufacturers, their respective lessors, commercial airlines and air cargo carriers, to aftermarket MROs.

Because this market has crossovers with the general engine business, for ease, I have outlined below an analysis of the latter industry:

Competitive rivalry

The aircraft engine industry is capital intensive, and there is a requirement for high investment in advanced technology and research and development. Four dominant players operate in this oligopolistic global industry: CFM International (CFMI), Rolls-Royce, General Electric, and Pratt & Whitney.

Each has the proven capability to design, develop, and product large gas turbine aircraft engines, and also run an engine leasing component as part of its business. No single manufacturer dominates the industry, so balance fuels the rivalry.

Competition in the primary market for aircraft engines is intensified by the link to the secondary market for engine part sales and services. Access to the secondary market is dependent on achieving the original sale of new engines. In recent years, the intensity of competition has increased for a number of reasons. Each manufacturer has tried to improve its volumes and market share, but also gas turbine engines are now essentially a mature product, meaning the potential for technological differential advantage has been reduced.

Outside of competition among these couple dominant players, the emergence of China as an aviation and financial powerhouse – with all sorts of new Chinese airlines, lessors, and lenders – has created many opportunities, as well as unforeseen competition. The newer business models of certain large international airlines, and even some low-cost carriers, have also created competition issues for airlines far away that never existed before.

Power of buyers

With a low number of potential buyers of new aircraft, the buyers of aircraft engines are therefore essentially price makers. Moreover, as many airlines have become global carriers, the power of buyers has further increased in recent years.

Airbus and Boeing, both of which are engaged in price competition to defend market share, publish list prices for their aircraft but the actual prices charged to airlines vary. They can be difficult to determine but tend to be much lower (usually 50% lower) than the list prices.

As of the late 2000s, there appear to be polarizing coalitions forming between engine suppliers and aircraft manufacturers, such as Boeing and General Electric partnering for the upcoming Boeing 777X, and Airbus working closely with Rolls Royce for the Airbus A350-1000.

As for purchasing a particular aircraft or engine combination, the decision is a long-term one. This means that failure to secure an order may prevent an engine manufacturer trading with a particular airline for more than a decade. While the nature of the leasing business, in comparison, is less committal and more short-term, the selection of one engine type can lead to a domino effect, with other lessees following suit with the same selection.

Power of suppliers

The suppliers to the aircraft engine manufacturer, on the other hand, have limited power. With hundreds of different suppliers of components like nuts and bolts and electronic control systems, the power of the many smaller companies, which comprise most of the supplier base, is vastly reduced.

The most powerful suppliers are those involved in the supply of high specification electronic control equipment. However, with engine manufacturers that adopt dual-sourcing strategies using a range of alternative supply sources, supplier power tends to be suppressed.

Threat of entry

While not impossible, entry to the aircraft engine industry is extremely difficult. The powerful combination of advanced specialized knowledge of design, high costs of R&D, and strong brand loyalty among customers, create significant barriers to entry.

However, in recent years, the industry has seen MROs step into the engine leasing space, offering more comprehensive solutions in order to claim their share of the market. Using their indepth knowledge of engines to offer one-stop services, MROs are giving traditional engine lessors a run for their money. While MROs have been offering costumers leasing options for quite some time now, the move to offer non-MRO customers the same kinds of services is a relatively new strategy that companies like MTU9 are pioneering. This movement may be in reaction to OEMs and aircraft engine lessors like Willis Lease, which have penetrated the aftermarket with similarly integrated, wide-ranging support packages.

Threat of substitutes

There is no clear, perfect substitute for an aircraft engine at the moment, and the threat of substitutes for air transport itself is minor. Although digital replacements for in-person meetings and the growth of other forms of high-speed transport may affect travel decisions, it is unreasonable for these alternatives to trump the demand for air travel.

In sum, this industry analysis shows us that the commercial aircraft engine business is highly competitive, with the buyer possessing and exerting a very powerful influence upon the rest of the supply chain. The high barriers to entry and the low threat of substitutes suggest that existing players will continue to compete among themselves for business.

However, as the industry landscape and customer cost-sensitivities change, a window opportunity opens up for independent, specialized engine lessors that are able to tailor to customer needs and compete with large-scale incumbents and international entrants.

9 In late-2013, MTU formed two joint ventures with Sumitomo (MTU Maintenance Lease Services and Sumisho Aero Engine Lease) in a bid to better serve the growing demands of the industry by offering a wider range of services, which span the entire lifecycle of an aircraft engine.

Who is Willis Lease Finance?

More than 30 years ago, Charles F. Willis, who is the the first entrepreneur to pioneer the business of jet engine leasing, launched Willis Lease Finance Corporation. The company operates in aviation services, specializing in leasing spare engines and other aircraft-related equipment to commercial airlines, engine manufacturers, and MROs worldwide.

The majority of its competition consists of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs)10, which, in most cases, deal only with their own engine products. By contrast, Willis Lease offers a broad product line, consisting of noise-compliant Stage III commercial jet engines manufactured by CFMI, General Electric, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, and International Aero Engines. These engines generally may be used on one or more aircraft types and are the most widely-used engines in the world, powering Airbus, Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, Bombardier, and Embraer aircraft.

Willis Lease has one of the largest and most diverse engine portfolios in the industry (more than $1 billion in assets), focusing on popular commercial jet aircraft engines used on leading aircraft. As of date, it has successfully purchased, leased, and sold more engines in more countries over a longer period of time than any independent competitor.

Much of its recipe for success has been accredited to strong capital availability, excellent customer relationships, order stability with major manufacturers, customer-driven engine pooling, and a solid management team.

Leasing

Willis Lease provides both short-term operating leases and sale/leaseback financing:

- Short-term operating lease:

- Unlike in finance or capital leases, in operating leases the lessor assumes the risks and benefits with owning the asset.

- A lessee will show the lease payment as an expense on its income statement, while the lessor depreciates the asset and shows a gain or loss upon sale of the asset.

- Operating leases are short-term, typically less than 75% of the anticipated useful life of the asset, and provide cash flow benefits compared to finance leases.

- Sale/leaseback:

- In a sale/leaseback transaction, an asset is sold to a leasing firm and then immediately leased back to the seller.

- This type of lease is usually long-term and is employed to free up capital for operations and transfer the residual value risk to the lessor.

Engine pooling

Willis Lease is a pioneer in establishing cooperative engine sharing pools. The North American engine sharing agreement, covering more than 600 aircraft, includes Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, Delta Airlines, Enerjet, Southwest Airlines, West Jet, and AirTran covering CFM56-7B engines used to power Boeing 737 NG aircraft.

10 An OEM is a company that makes a part or subsystem that is used in another company’s end product (e.g. General Electric GEnx engine used as part of the Boeing 747 Dreamliner aircraft).

What are its competitive strategies? How does it tackle the aforementioned challenges?

Independent ownership

The independent ownership of Willis Lease allows it to meet customer needs without regard to any potentially conflicting demanding to use their engines or services. As an independent public company, it has the ability to work with customers to accurately identify their needs and provide them with the engines, equipment, and services that are best tailored to those needs.

Many of the larger aircraft engine leasing companies with which it competes, such as RollsRoyce, GE, and Pratt & Whitney, are owned in whole or part by aircraft engine manufacturers. As a result, the leasing parts of their businesses are inherently motivated to sell to customers the aircraft equipment that is manufactured by their owners, regardless of whether that equipment best meets the needs of their customers.

“Triple-net” operating leases

All of Willis Lease’s leases to air carriers, manufacturers, and MROs are operating leases, which afford lessees greater fleet and financial flexibility and the availability of short- and long-term leases to better fit their needs. Operating lease rates are generally higher than finance lease rates, in part because of the risks associated with the residual value.

All of its current leases are triple-net operating leases, which require the lessee to make the full lease payment and pay any other expenses associated with the use of the engines, such as maintenance, casualty and liability insurance, sales or use taxes, and personal property taxes. The leases also contain detailed provisions specifying the lessee’s responsibility for engine damage, maintenance standards, and the required condition of the engine upon return at the end of the lease.

During the term of the lease, Willis Lease requires the lessee to maintain the engine in accordance with an approved maintenance program (certified by the FAA or its foreign equivalent) designed to meet the appropriate regulatory requirements. In addition, when an engine becomes off-lease, it undergoes detailed inspection to verify compliance with lease return conditions.

In general, the company places great attention on its lessees and its emphasis on maintenance and inspection helps to preserve residual values and recover its investment in leased engines. As we covered earlier, this is particularly important to engines, the full value of which can be recovered any time during the life cycle through means of careful maintenance and asset management.

Joint ventures with Chinese and Japanese partners

Over the next twenty years, China is expected to be the world’s fastest growing aviation market. Based on industry forecasts and conservative assumptions, the size of the spare engine market in China over the next five years is expected to reach $2 billion.

Willis Lease has formed two very significant joint ventures with formidable partners in Japan and China, in order to tap low-cost financing and capture greater market share:

- CASC Willis Engine Lease Company (CASC Willis)

- 50/50 JV formed in June 2014 with China Aviation Supplies Import & Export Corporation Limited (CASC), China’s leader in aviation supplies trade

- The JV is dedicated to supplying Chinese airlines with the best engine support solutions and creating an engine resource sharing platform. It will focus on meeting the fast-growing demand for leased commercial aircraft engines and aviation assets in mainland China.

- Its initial focus is investing in current generation engines powering the fleet of narrow body and wide body commercial aircraft in China. However, the JV fully expects to migrate into new technology engines such as CFM International’s LEAPx, General Electric’s GEnx and GE9X and Pratt & Whitney’s GTF, once those engines become more widely popular.

- CASC Willis is established within the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) 11 in order to take advantage of the evolving governmental support programs offered to companies there.

- Willis Mitsui & Company Engine Support Limited (WMES)

- 50/50 JV formed in May 2011 with Mitsui & Co., Ltd., one of the largest general trading companies in Japan

- The JV was formed for the purpose of acquiring and leasing jet engines (IAE V2500-A5 and General Electric CF34-10E jet engines, the former of which is used on the Airbus A320 family of aircraft and the latter on Embraer E190 and E195 aircraft).

- The powerful combination of Willis Lease’s deep knowledge of the jet engine leasing marketing and Mitsui’s equity capital distribution, ability to provide attractive financing, and its global network, translate to a number of competitive advantages in the engine leasing market.

Willis Aero

In November 2013, Willis Lease launched Willis Aeronautical Services, Inc. (Willis Aero), whose primary focus is the sale of aircraft engine parts and materials through the acquisition or consignment from third parties of aircraft and engines.

By enhancing the end-of-life capabilities of its equipment, Willis Lease has positioned itself to establish a presence in the supply chain business. It is now better equipped to manage the full lifecycle of its lease assets, enhance the returns on its engine portfolio, and create incremental value for its shareholders. Aero Willis was founded on the commitment to doing things right by our customers, for such a value proposition aligns the goals of the engine lesser with those of the aircraft operator.

Willis Aero, which is run by 4 senior managers with a combined 75 years in the aerospace industry, has expertise in longstanding industry relationships, insight on aircraft and engine life cycles, value fluctuations, asset procurement, and asset valuation. It has the ability to both attractively procure and dispose of assets throughout their useful life cycle. By developing close working relationships with both airlines and MROs, it can successfully forecast short- to midterm demand. This enables the business to fulfill MRO parts and engine overhaul requirements, as well as airline lease requirements prior to aircraft-on-ground12 situations or increased capacity demand.

In 2015, Willis Aero’s spare part sales increased 75% to $15.6 million, and its margin improved 143% to $3.5 million, compared to 2014. This business has progressed nicely since late-2013, and the company has plans to expand different strategies in the coming years to capture more of Willis Aero’s potential.

11 Officially launched in September 2013, SFTZ is the first free-trade zone in mainland China. The transportation industry is one of the specific industries that received approval.

What are its competitive concerns?

Advances in the aftermarket

Despite Willis Lease’s efforts to expand its supply chain via Willis Aero, this recent launch is simply one strategy in response to increased competition in the end-of-life engine leasing market. Other lessors, too, have recognized the need to diversify their services, with some choosing to offer engine and landing gear exchange services. For instance, Rolls-Royce’s introduction of TotalCare acts like an insurance policy, in which the engine manufacturer takes responsibility for keeping an engine on wing in return for a dollar-per-engine-flying-hour fee.

As for competition from the MRO front, a wave of technological change is about to break on the aviation aftermarket. By 2020, most companies in the MRO sector will make pervasive use of big data, aircraft health monitoring, and predictive maintenance systems. The way that MROs touch the aircraft will change with wearable and other new repair technologies and additive manufacturing (3-D printing).

According to Oliver Wyman’s 2015 MRO Survey, it is anticipated that these advances could cut 15 – 20% of MRO spending from the aftermarket, and spawn new business models and revenue streams. In total, this would amount to a redistribution of $10 billion to $15 billion of value among current industry players and entice new competitors to enter.

Entry of Asian competitors

New entrants are also expected to increase competition, with Japanese lessors becoming increasing active over the past 3 – 4 years. While Willis Lease may be able to succeed against more established competitors due to the sheer size of the segment, the key concern for those lessors remains in growing the required level of expertise over a number of years.

Heightened competition from Asia continues to appear in other forms. For instance, many current companies have been struggling to grow through new sale/leasebacks because of factors like aggressive pricing from China. Thus, it has become ever more important to explore other ways of finding aircraft and engines through forming strong relationships with airlines, which Willis Lease will have to continue capitalizing on in order to grow successfully.

12 “Aircraft on Ground (AOG)” indicates that a problem is serious enough to prevent an aircraft from flying

What are its industry concerns?

Changing leasing paradigm

Engine lessors are adapting their business models to adjust to the shift in how airlines operate aircraft, as well as to increased competition in the leasing space. While the overall demand of acquiring engines on lease remains strong and is expected to continue growing, the paradigm of the sector has drastically in recent years.

A fundamental change in how airlines lease engines was spurred by the 2008 financial crisis as a turning point. Before 2008, engine lessors like Engine Lease Financial Corp. would typically put an engine on sale/leaseback for 6 – 8 years, returning from lease before going back on another lease for 3 – 4 years before going into a short-term market. Since 2008, airlines have become savvier managing their fleets and utilizing the leasing community to their advantage. Now the industry is seeing more aircraft on a first lease for 10 – 12 years, with no secondary base before eventually going into a green time and part-out situation13 .

Trends in global aviation

In the past few years, the global aviation and aviation finance industries have undergone profound changes, and most likely will continue to evolve in the years to come:

- Industry consolidation

- Airlines as a group have become extremely profitable, and the consolidation of airlines, lessors, and supply chain has continued to shift the competitive landscape.

- To a large degree, the industry’s low margins are driven by its fragmentation and the resulting overcapacity in many markets

- Still, US carriers have been able to improve their financial performance dramatically, primarily through bankruptcy restructuring and a series of major mergers.

- Given this dwindling number of engine consumers in the market, their aggregate bargaining power will only continue to strengthen. Thus, engine lessors will have to adapt in ways to avoid disadvantageous negotiations in price and engine type with these few, dominating brands

- Growth of low-cost carriers (LCCs)

- Measured by revenue, the global airline industry has doubled over the past decade, from $369 billion in 2004 to $746 billion in 2014, according to the IATA.

- Much of that growth has been driven by LCCs, which now control some 25% of the worldwide market and which have been expanding rapidly in emerging markets.

- These LCCs also tend to be price-sensitive and lean towards engine leasing, so lessors like Willis Lease will have to make greater note of the credit risk and financial standing of the lessee before entering into any significant lease transaction.

- Rising jet fuel prices

- In 2015, when oil prices plummeted, many thought that the airline profitability boost was going to last forever. However, the more cautious ones speculated that the lower price of fuel may change industry dynamics over time, and the benefits may be smaller than others believe.

- Now, with fuel costs rising above the levels of where they had started falling two years ago, airlines face a fresh test of their financial resilience amid rising fuel prices and labor costs.

- As fuel prices rise, airlines must adjust their budgets accordingly; with more funding funneled toward gas, less is available for overall growth, including capital investment in engines and other aircraft equipment.

13 “Green time” refers to the remaining useful maintenance life of an aircraft, engine, or component. When the value of parts is greater than the value that can be realized by selling the whole asset, the “part out,” or the teardown, disassembly, repair, and sales of used aircraft and engines, may be the more practical strategy.

Sources

- Willis Lease 2016 Fact Sheet:

http://www.willislease.com/pdf/corporate-factsheets/WLFC%203Q16%20draft%202.pdf - Willis Lease 2015 Annual Report:

https://www.willislease.com/pdf/annual-reports/2015_Annual_Report.pdf - Facts about Aircraft Engine Leasing Returns:

http://www.jetenginesolutions.com/factsaboutaircraftleasing.php - Engine Maintenance Concepts for Financiers:

http://www.aircraftmonitor.com/uploads/1/5/9/9/15993320/engine_mx_concepts_for_fin anciers___v2.pdf - A New Look Engine Leasing Market:

http://www.mro-network.com/leasing-financial-services/new-look-engine-leasing-market - Competition between Airbus and Boeing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Competition_between_Airbus_and_Boeing

- Boeing: Current Market Outlook (2016 – 2035): http://www.boeing.com/resources/boeingdotcom/commercial/about-ourmarket/assets/downloads/cmo_print_2016_final_updated.pdf

- Understanding the Business of Aircraft Leasing:

https://revenuesandprofits.com/understanding-the-business-of-aircraft-leasing/ - How does the Airplane Leasing Business Work?:

https://www.quora.com/How-does-the-airplane-leasing-business-work-Why-do-airlinesbuy-the-planes-then-sell-them-to-a-leasing-company-and-then-lease-it-back - Rolls-Royce Case Study: Porter’s Five Forces Model:

http://businesscasestudies.co.uk/rolls-royce/competing-within-a-changing-world/portersfive-forces-model.html#axzz3td1p6kOL - Willis Lease and China Aviation Supplies Corp Announce Engine Leasing Joint Venture: https://globenewswire.com/news-release/2014/06/09/642677/10084928/en/Willis-Leaseand-China-Aviation-Supplies-Corp-Announce-Engine-Leasing-Joint-Venture.html

- How Engine Lessors Adapt Strategy to Match Changing Market:

https://aviationweek.com/special-topics-pages/optimizing-engines-through-lifecycle/how-engine-lessors-adapt-strategy-match - Aftermarket Revolution:

https://www.aerosociety.com/news/aftermarket-revolution/ - 2015 Aviation Trends:

http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/trends/2015-aviation-trends - Jon Sharp: An Overview of the Aircraft Engine Aftermarket in mid-2016

http://www.elfc.com/press-release—july-27th-2016—an-overview-of-the-aircraft-engineaftermarket-in-mid-2016.asp - Jon Sharp: Airline Economics in 2015

http://www.elfc.com/the-face-of-aviation-2014-jon-sharp.asp